Return to the Our Other Ancestors page - or - return to A McLaren Migration homepage.

Robert Arthur Dixon

Biography

In 1834 Robert Dixon, freeholder of the Lislea estate in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, departed the family home with his pregnant wife and two young sons, intent on immigrating to Australia. Soon after their departure they were shipwrecked and returned to Ireland, where they filed suit against the ship owners in Liverpool. While the litigation was in progress Robert's third child, Robert Arthur Dixon, Jr. was born, "on shipboard" according to the family bible, at Belfast on November 8th.

In August of 1837, now with a fourth child (their first daughter, Jane Caroline, born in January 1836) they resumed their journey. In the intervening years however, for reasons unknown, they had changed their destination to the United States. They boarded the ship Sheridan in Liverpool, sailed to New York City, and then took the Erie Canal to Chicago where they settled about 25 miles west of that city in the area now known as Downers Grove.

Robert Dixon, Jr. was my great grandfather. He was two years old during the transit from Ireland to Chicago. He met and married his wife, Sarah Jane Rowland, in Downers Grove. Absent that shipwreck I wouldn't be here and you wouldn't be reading about this fascinating gentleman. Life is random.

Robert Arthur's father was one of the earliest settlers of Illinois, taking up government land and starting a farm. As the settlement grew, he was elected Justice of the Peace for many years and was the first judge in Downers Grove. Four more children, two boys and two girls, were born to the family in Illinois, the last in 1847. Then Robert's father, Robert Sr., died suddenly in August of 1850, at the age of forty five. Robert Jr. was fifteen.

No child expects to lose his father that young, but in those days a fifteen year old farmer's son was essentially an adult. With his two older brothers, ages seventeen and eighteen, they were quite capable of maintaining the farm and caring for their mother and the younger siblings. Robert's older brother James married in 1857 and then William married in 1859. In the 1860 Census Robert's mother Mary is "head" of the household and twenty five year old Robert is the man of the house, farming with his five younger siblings.

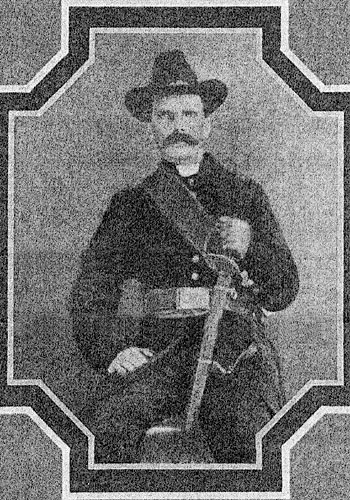

In January of 1861 the southern states began to secede from the Union and in April the Civil War began. Robert Dixon Sr. had been a staunch Abolitionist and one of the leaders of the Underground Railroad at a time when those sentiments required great courage. A decade after his passing Robert Senior's children followed in his footsteps. His four oldest sons all volunteered and served in the Union Army. Robert Jr. and his older brother William both enlisted on 3 September 1861. They were assigned to Company "E" of the 55th Infantry Regiment, Illinois in October. William resigned, for unknown reasons, in March of 1862, but Robert continued his service. Older brother James enlisted in August of 1862 and younger brother Charles, who was too young at the start of the war, enlisted in October of 1864.

During the war the 55th Infantry was part of General Sherman's march from Atlanta to the sea. They engaged in more than twenty pitched battles and dozens of other skirmishes. In the battle of Shiloh, in April of 1862, the 55th Infantry distinguished themselves against a vastly superior force, but they lost ten officers and 102 others killed or mortally wounded; probably one quarter of their total compliment. Overall, the most destructive of those battles was Kenesaw Mountain, in June of 1864, where Sherman lost nearly three thousand men.

Another of their battles lets us revisit the thought that life is random: The battle of Missionary Ridge. General Sherman's forces drove the Confederate Army from the area around Chattanooga, Tennessee in October and November of 1863. Among the Confederate casualties of that battle was my maternal great grandfather Barney Burch. He received a wound that led to paralysis and eventually caused his death. However, Barney lived to be eighty two years old and sired twelve children, including my grandmother, so it's hard to hold a grudge. But please note that two of my great grandfathers stood on opposite sides of that ridge, one in Blue and one in Grey, and if one of the men in Blue had been a better shot I wouldn't be here.

Another of their battles lets us revisit the thought that life is random: The battle of Missionary Ridge. General Sherman's forces drove the Confederate Army from the area around Chattanooga, Tennessee in October and November of 1863. Among the Confederate casualties of that battle was my maternal great grandfather Barney Burch. He received a wound that led to paralysis and eventually caused his death. However, Barney lived to be eighty two years old and sired twelve children, including my grandmother, so it's hard to hold a grudge. But please note that two of my great grandfathers stood on opposite sides of that ridge, one in Blue and one in Grey, and if one of the men in Blue had been a better shot I wouldn't be here.

Robert served almost exactly four years, with only one thirty day furlough in the spring of 1864. His regiment re-enlisted after three years of service, with the understanding that they would elect their own officers, and Robert was elected Lieutenant. He mustered out as a Captain on 14 August 1865, one of only ten men in his company that had never been wounded.

After the war Robert and his brothers returned to Downers Grove. Their mother, Mary Elizabeth (Wilson) Dixon, died in 1865, about the time of their return. She was fifty six years old. The older sons were apparently no longer interested in farming and the family farm passed to John, the youngest brother (then 22 years old). Robert entered the wood and coal business in Chicago. He then formed a partnership with his older brothers, William and James, to manufacture window sashes and blinds. Younger brother Charles was also in Chicago manufacturing mouldings.

On Christmas day of 1869 Robert married Sarah Jane Rowland at the home of her father in Downers Grove. In the 1870 Census he and his wife are living in Chicago with his brother James and his family. Brother William and his family are next door.

The Dixon brothers' business was later destroyed by the economic crisis of 1873 and Robert returned to Downers Grove. There he engaged in general merchandizing with his brother-in-law Peter Rowland.

Between 1872 and 1878 Robert and Sarah had four children, two girls and two boys. They were active members of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Downers Grove and Robert was "an active and energetic Republican." By 1881 he had located in Lisle, Illinois, just West of Downers Grove, where he ran a general store doing good business. But Robert had decided to "move on." (The fact that Robert Sr. was the freeholder of the Lislea estate in Ireland and Robert Jr. is doing business in Lisle, Illinois is pure coincidence.)

The Dakota Territories had been available for settlement for many years, but it was the discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874 that energized the migration. By 1877 the railroads decided it would be profitable to extend their lines into the Territory and thus began a land "boom" that lasted from 1878 to 1887. Robert Dixon decided he wanted some of that land and in October of 1882 he boarded a train for Howard, 600 miles west northwest of Lisle, in what is now South Dakota.

He arrived in Howard on October 11th and began an odyssey involving 450 more miles of train travel, nine stops and countless miles of walking or riding horses or buggies. The details of his search and subsequent claim of land come from letters exchanged between Robert and his wife. The originals are in possession of an Illinois cousin, Dean Essig, and he was kind enough to send me copies. Follow the link Robert and Sarah's Letters (This is an Adobe PDF® file; use your back button to return to this page) to find transcripts of their letters and a map of the area Robert scoured.

Robert started by looking for "free" land under the Homestead Act. The head of a household would be granted a quarter section of land (160 acres, ½ mile square) if he would live on the property and improve it over a period of five years. He quickly concluded that "I am a year too late." All land within 10 to 15 miles of the railroads was taken and all the free claims within 20 miles, and he certainly wasn't the only one riding the rails in search of something suitable. "I have a thorough knowledge of the county and all I have to do is to locate. I find this a hard thing to do, my heart sometimes almost fails me . . . I am trying to trust in Him . . . with His help I will make no mistake." Since free claims were out of reach, he decided to "preempt" a claim by paying a small fixed price per acre. As a Civil War veteran, he was also entitled to claim a second quarter section with a "soldier's filing" and expressed great concern that Sarah forward his discharge papers to prove his eligibility.

After searching for almost three weeks, on October 28, 1882 Robert finally filed a preemptive claim to one quarter section and a soldier's claim to a second quarter. The claims formed the south half of Section 6 in what would eventually become Dixon Township. (A township is a square plot of land containing 36 sections, and is, therefore, six miles on a side. Section 6 would be the northwest corner of that square.) This claim was twelve miles due south of the new railroad station in Henry, just west of Watertown. The story goes that the wheel of his buggy struck a grass covered stone, which proved to be the U.S. survey marker for the land. After filing his claim he returned to find a prairie fire had burned the area and it took him some time to locate his land.

Preemption required Robert to move onto one claim immediately and "prove" he lived there for six months. He would then move to the second quarter, his soldier's filing, and repeat the process. So he proceeded to build a structure he eventually called "Big Shanty" on his preemption. Let's be clear: His claim is twelve miles from the railroad station, it's almost November and he's going to build a place to live alone through the Dakota winter. Robert will be forty eight years old in November; think about that.

As he starts construction, each trip to the hardware store is a twelve mile hike, then hire a wagon to haul the supplies and return to the shanty. In one instance the store in Henry was out of nails, so he rode the train eighteen miles to Watertown. "I am now preparing to build a big shanty. The lumber will cost over $100.00. This lumber I will want for a stable when our house is built. I have spent up to the present time $80.00 leaving me $70.00 on hand. I bought me an overcoat for $8.00." He completed the shanty, 24 x 28 feet, in mid-November and prepared to hunker down for the winter. His nearest neighbor was 2 ½ miles away and he was the only resident in Dixon Township during that winter. Sarah expressed legitimate concern over his plan: ". . . how in the world you are going to contrive to move into & live in that shanty up there without anything to move I cannot understand. Will you buy a stove & a blanket & try soldier's life again?" Indeed. Her letters also mention his purchase of a gun and some "fox traps," so he was obviously positioning himself as a "hunter/gatherer" in his new digs.

It was winter, it was South Dakota. Sarah expressed her concern in early February: "Mr. McMillan tells me that all the R.R.'s up in Dakota & Minn. he thinks are blockaded, and have been so since Tuesday, so I suppose that will account for my receiving no letters this week … If I only knew you had provided yourself with plenty of provisions & coal to last through the stormy season I think I would not worry but I fear you have not . . . We are having an exceptionally cold stormy winter here. Yesterday morning Mr. Fret Hatch's thermometer stood at 26 deg below zero."

Robert survived the winter and in March of 1883 returned to Lisle to gather his family, his possessions and lumber for another house. He would soon "prove" his first claim by having lived in the shanty for six months. Now he needed to establish residence on the soldiers filing. His family would move into the shanty that spring while they built a new home on the second quarter during the summer. His daughters were four and eleven years old, his sons were seven and nine. Other settlers had moved into the area by then and in May a Sunday-school was organized and held in the Dixon shanty. By July of 1884 a public school was organized on Section 5, next door. The shanty was also used for services by the Free Methodist church.

Not everyone claiming land in the Dakotas was as determined as Robert. Many claims were forfeited when the claimants couldn't or wouldn't make the sacrifices necessary to hold on. At some point during this process Robert purchased a relinquishment on a tree claim, another quarter section adjacent to his original claims, which brought his total holdings to 480 acres.

In 1887 the Duluth, Watertown and Pacific Railroad Company began construction of a rail line that would eventually pass within 500 yards of the Dixon home. Progress was slow, as all the graders and scrapers were horse drawn, but the importance of a rail line this close to a farm can't be overstated. After the rails were down the railroad created a station which became the center of the town of Vienna (pronounced "v-eye-enna" in South Dakota). Vienna was less than a quarter of a mile west of the Dixon land. The Railroad became the Burlington Northern and Vienna grew to a town of almost 500 folks in the early 1900's. Robert had been convinced a rail line would be built somewhere in the area, but the exact location was anybody's guess and nothing is certain. There is no substitute for blind luck.

Dixon Township was named for Robert in 1889, the last township organized in Hamlin County. Robert was a member of its first board of supervisors and was continuously part of township and school affairs. He served as a commissioner of Hamlin County for six years and, in 1891, he was chosen state senator for the 27th District, serving one term. (The Dakota Territory became North and South Dakota in November of 1889. State senators were originally appointed, rather than elected.) He was a Populist, an upholder of prohibition and equal suffrage.

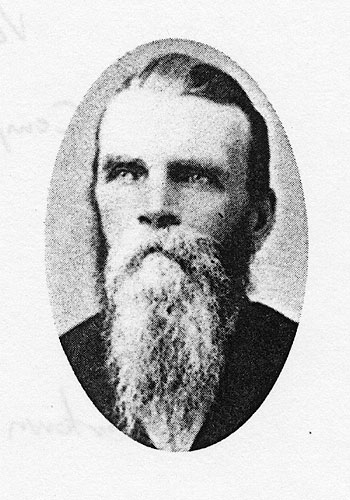

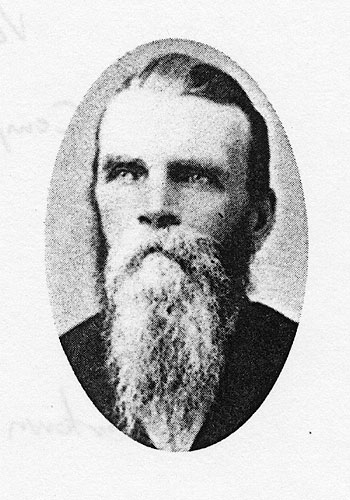

This photo was in the Biographical Directory of the South Dakota legislature, so it was taken around 1891, when Robert was 55 years old. If we apply today's grooming standards, the beard isn't particularly attractive. But then I remember my grandfather, Anthony Winchester, emerging from the bathroom after using his straight razor. (You remember straight razors - sharpened with the leather razor strap. And the cup of shaving soap, with the shaving brush.) His face would be dotted with scraps of toilet paper and blood; there were patches of long hair on his neck that he either hadn't seen or he chose not to risk slitting a major artery; and it was hours before the dots of paper came off. And Anthony had a sink with hot running water. Robert Dixon would have had to heat the water and then use a lamp or candle to provide light if he was shaving before sunrise. Suddenly the beard looks just fine.

This photo was in the Biographical Directory of the South Dakota legislature, so it was taken around 1891, when Robert was 55 years old. If we apply today's grooming standards, the beard isn't particularly attractive. But then I remember my grandfather, Anthony Winchester, emerging from the bathroom after using his straight razor. (You remember straight razors - sharpened with the leather razor strap. And the cup of shaving soap, with the shaving brush.) His face would be dotted with scraps of toilet paper and blood; there were patches of long hair on his neck that he either hadn't seen or he chose not to risk slitting a major artery; and it was hours before the dots of paper came off. And Anthony had a sink with hot running water. Robert Dixon would have had to heat the water and then use a lamp or candle to provide light if he was shaving before sunrise. Suddenly the beard looks just fine.

Robert was not a large man. His Civil War records describe him as 5 foot 3 ½ inches tall and 135 pounds. He was the shortest of the four brothers with war records; but the tallest, William, was 5 foot 6 inches. His physical stature obviously didn't limit his status. He was elected to an officer's position during the Civil War; he was a successful businessman, literally a pioneer in the Dakota Territory, then was elected or appointed to several political offices.

It had been a fascinating but strenuous life. In February of 1892, at age fifty six, Robert submitted a Declaration for Invalid Pension to the U.S. Government. The English language confuses me at times, and I couldn't imagine applying for a pension that wasn't valid. It took a while to realize that Robert was not asking for an in-va-lid pension, he was declaring that he was an in-va-lid. The details of his application and subsequent pension payments can be found here: Pension Synopsis. Suffice it to say he was not well and his condition worsened over time. By 1895 he declared himself "totally incapacitated for the performance of any manual labor," and his declaration was supported by doctors and other witnesses.

One portion of the application struck me, as Robert listed his various physical ailments: "In the fall of 1884 he received an accidental gunshot wound on the right side of his head and in his right shoulder from which he is threatened with paralysis." Four years of Civil War combat, dozens of major battles, one of ten men in his company without a scratch, and he gets shot at home in South Dakota by accident.

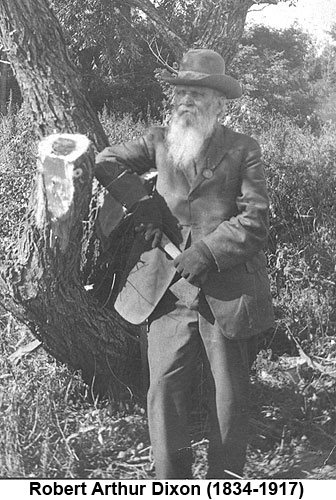

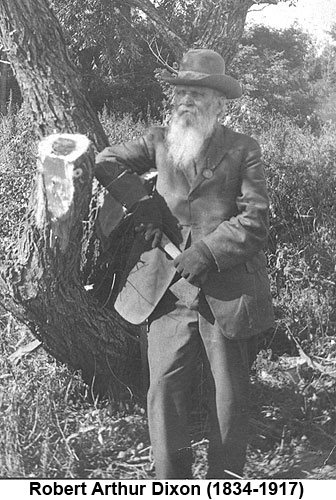

Of course, he only lived twenty five years after declaring himself an invalid, dying in his home in February of 1917 at the age of eighty two. There he was surrounded his wife, both of his sons, and one daughter with her husband (my grandparents), all living on the Dixon compound, the site of Robert's original homestead claim. He was buried in the Dixon "New Hope" Cemetery on the northeast corner of his land, joined later by his wife and son Robert Rowland Dixon.

Of course, he only lived twenty five years after declaring himself an invalid, dying in his home in February of 1917 at the age of eighty two. There he was surrounded his wife, both of his sons, and one daughter with her husband (my grandparents), all living on the Dixon compound, the site of Robert's original homestead claim. He was buried in the Dixon "New Hope" Cemetery on the northeast corner of his land, joined later by his wife and son Robert Rowland Dixon.

The Dixon land is still being farmed, though Vienna is a shadow of its former self. Robert's descendants have moved on and followed a variety of professions, just like Robert. He was a pioneer, and we owe him a tremendous debt. Calling his cemetery "New Hope" seems entirely fitting. Our good lives were born in Robert's hard work. We'll let Robert have the last word:

"Dear wife our lives are short and are passing away fast, our work is not for ourselves but for the children that God has given us. The struggle is hard some times but with God's blessing to cheer us and our love for each other and our little ones we can be happy here in His sin wrenched world and finally gain that rest that remains for the people of God. [October 31, after claiming the land] You ask me about the land. I can say it is good, very good. It is strange how I came to get this land, I believe that God sent me here and I receive it as coming from Him. I thank God for His goodness to me in sending me to where I am so well pleased." [Nov 15th 1882]

Return to the

Our Other Ancestors page - or - return to

A McLaren Migration homepage.

This site, A McLaren Migration, is maintained by David J. McLaren.

Updated May 19, 2015

Copyright © 2021 David J. McLaren, all rights reserved.

Commercial use of the material on this site is prohibited.

Another of their battles lets us revisit the thought that life is random: The battle of Missionary Ridge. General Sherman's forces drove the Confederate Army from the area around Chattanooga, Tennessee in October and November of 1863. Among the Confederate casualties of that battle was my maternal great grandfather Barney Burch. He received a wound that led to paralysis and eventually caused his death. However, Barney lived to be eighty two years old and sired twelve children, including my grandmother, so it's hard to hold a grudge. But please note that two of my great grandfathers stood on opposite sides of that ridge, one in Blue and one in Grey, and if one of the men in Blue had been a better shot I wouldn't be here.

Another of their battles lets us revisit the thought that life is random: The battle of Missionary Ridge. General Sherman's forces drove the Confederate Army from the area around Chattanooga, Tennessee in October and November of 1863. Among the Confederate casualties of that battle was my maternal great grandfather Barney Burch. He received a wound that led to paralysis and eventually caused his death. However, Barney lived to be eighty two years old and sired twelve children, including my grandmother, so it's hard to hold a grudge. But please note that two of my great grandfathers stood on opposite sides of that ridge, one in Blue and one in Grey, and if one of the men in Blue had been a better shot I wouldn't be here. This photo was in the Biographical Directory of the South Dakota legislature, so it was taken around 1891, when Robert was 55 years old. If we apply today's grooming standards, the beard isn't particularly attractive. But then I remember my grandfather, Anthony Winchester, emerging from the bathroom after using his straight razor. (You remember straight razors - sharpened with the leather razor strap. And the cup of shaving soap, with the shaving brush.) His face would be dotted with scraps of toilet paper and blood; there were patches of long hair on his neck that he either hadn't seen or he chose not to risk slitting a major artery; and it was hours before the dots of paper came off. And Anthony had a sink with hot running water. Robert Dixon would have had to heat the water and then use a lamp or candle to provide light if he was shaving before sunrise. Suddenly the beard looks just fine.

This photo was in the Biographical Directory of the South Dakota legislature, so it was taken around 1891, when Robert was 55 years old. If we apply today's grooming standards, the beard isn't particularly attractive. But then I remember my grandfather, Anthony Winchester, emerging from the bathroom after using his straight razor. (You remember straight razors - sharpened with the leather razor strap. And the cup of shaving soap, with the shaving brush.) His face would be dotted with scraps of toilet paper and blood; there were patches of long hair on his neck that he either hadn't seen or he chose not to risk slitting a major artery; and it was hours before the dots of paper came off. And Anthony had a sink with hot running water. Robert Dixon would have had to heat the water and then use a lamp or candle to provide light if he was shaving before sunrise. Suddenly the beard looks just fine. Of course, he only lived twenty five years after declaring himself an invalid, dying in his home in February of 1917 at the age of eighty two. There he was surrounded his wife, both of his sons, and one daughter with her husband (my grandparents), all living on the Dixon compound, the site of Robert's original homestead claim. He was buried in the Dixon "New Hope" Cemetery on the northeast corner of his land, joined later by his wife and son Robert Rowland Dixon.

Of course, he only lived twenty five years after declaring himself an invalid, dying in his home in February of 1917 at the age of eighty two. There he was surrounded his wife, both of his sons, and one daughter with her husband (my grandparents), all living on the Dixon compound, the site of Robert's original homestead claim. He was buried in the Dixon "New Hope" Cemetery on the northeast corner of his land, joined later by his wife and son Robert Rowland Dixon.